Wednesday, August 09, 2006

A-Rod, Love Him or Hate Him

It's a sunny Monday afternoon in July, hours before game time, in New York's Central Park, and Alex Rodriguez is soaking up some rays. Shirt off, leaning against a rock, laughing and talking with his wife, Cynthia, playing in the grass with his young daughter, Natasha. It must be a sweet moment for them, kissed by the sun and the breeze, alone and together.

But we don't see it like that. We see it as a distracted prelude to three errors the same night against the Toronto Blue Jays. The Jay Greenbergs (New York Post columnist) among us see it as "an unnecessary ultraviolet broil" that leaves him unprepared to do his job, reminding us more of "well-heeled idiots in [a] beer commercial" than superstar third basemen. The Selena Robertses (New York Times columnist) among us see it as preening, a guy "perfectly coifed … flaunting pecs and abs as if awaiting an Abercrombie & Fitch talent scout." We see it as a moment to pounce.

This is how we do A-Rod.

He goes 3-for-10 as the A's sweep a weekend trip to the Bronx in June, and we call in to Michael Kay's radio show, saying he's not clutch, saying he's no Reggie, no Paul O'Neill. And the particularly agitated among us say he's no better than Danny Tartabull, a high-priced free agent who hit .252 in three-plus years with the Yankees in the mid-'90s.

Tartabull hit 262 home runs, and Alex has 452 at age 31. Rodriguez's career OPS is nearly one hundred points higher. He's the defending AL MVP. He's going to the Hall of Fame, and the other guy is fading into obscurity. The comparison is insane.

But this is how we do A-Rod.

He hits a come-from-behind grand slam and tops it with a single and a three-run jack in a 16-7 pasting of the Mets in early July, and the crowd at Yankee Stadium gives him a standing ovation, calls him out of the dugout for a tip of the cap after each home run.

But at the end of the night, after he grounds out to short in his last at-bat, Sean and Mike, two 30-something lifelong Yankee fans, stand in the concourse near the beer stand and tell me, Yeah, we get how good he is. We know we need him. But still, man, you have to admit, for a so-called great player, he f---ing sucks. To be honest with you, we f---ing hate him.

And this is how we do A-Rod.

How Do You Feel?

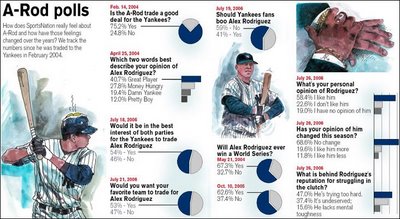

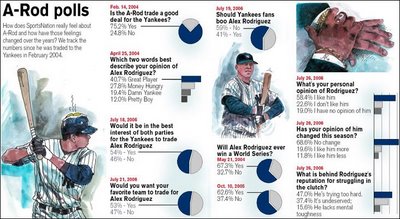

The boobirds have flocked to Alex Rodriguez at Yankee Stadium this season, but is that indicative of how all of SportsNation feels about No. 13? Register your vote as we take SN's temperature on A-Rod.We call him a choker and a poseur. We call for the Yankees to trade him. We beat him about the head with Jeter Sticks and Papi Clubs. We tease his look. We hyperparse his words. We downplay his every success, boo his every pop-up, and hiss his every miscue. "I've never seen a player this good this vilified," says Kay, who also broadcasts Yankee games for the YES network. "It's amazing to me."

We've all heard the standard reasons — resentment over his $252 million contract, envy of his talent, frustration that he doesn't exceed all our wildest expectations, a selective-memory perception that he's no good in the clutch and, of course, the fact that he's not Derek Jeter. All these explanations have validity, no doubt, but they don't fully explain the giddy, sometimes irrational, intensity of this thing we do. They don't get at the bile and the vitriol.

There's something more at work here. Rodriguez has had an ugly summer by his standards, but it ain't about that. It's about this, first, last and always: We think A-Rod's soft. We don't think he's tough enough to be our guy. We think he's weak.

We're not talking about the buddy-can-you-spare-a-dime, meek-shall-inherit-the-earth weak to which we routinely show charity. We're talking about the vulnerable, soft-underbelly sort of weak for which we in this "¿Quien es mas macho?" culture of American sport so often show contempt.

Part of it is on-the-surface, clichéd, stereotyped stuff. He's pretty like a model in a magazine, complete with pouty lips and brooding eyes. His swing, for all its oomph, is a long, delicate stem of a lily. He sees a psychiatrist … and talks about it. He has a life coach who sends him daily affirmations. He goes to art museums to gaze at the great works … and talks about that, too.

Some of it is on the field. Eighteen errors through 109 games this season, and some of them coming in jittery Knoblauchian bunches. An anemic .200 batting average in close-and-late situations so far in 2006.

Some of it is embedded in history. The undisputed iconic heart of the perception is the left-handed slap he made at the ball in Bronson Arroyo's glove, coming down the first baseline in Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the Red Sox. Curt Schilling called it a "bush league" play, and digitally altered pictures of A-Rod with a purse dangling from his wrist appeared on the Internet almost overnight. On the biggest stage of his playing life, Alex Rodriguez, AL MVP, became Smacky McBluelips, handbag-toting girly-man.

"It's ridiculous, but that play defines him in a lot of people's minds," says Alex Belth, author of the Yankee blog Bronx Banter. "It's become this monster, this thing that feeds on itself and will never die."

The slap — what he did do — is a kind of marker, too, for what he didn't do in the last four games of the ALCS, which is hit. At all (2-for-17 in the last four games). Clutch or otherwise. When the Yankees collapsed after being up 3-0 in the series, the slap, in all its perceived limp-wristedness, symbolized the soft hearts of the losers in contrast to the lionhearted history makers from Boston.

The real roots of the feeling are deeper, though. In the batting cage before his big game against the Mets on July 2, Rodriguez cracks balls to left and center. His swing has a long, level grace about it, but standing just feet from the cage you realize there is a genuine violence in it, too. The boom off his bat is merciless, instinctive, the bolt of a god.

Minutes later, standing in the hallway outside the Yankees' clubhouse, Rodriguez talks to reporters who've gathered at the news of his selection to the American League All-Star team. Someone asks whether he's surprised to have been voted to start on the team after all the booing he has been hearing this season.

"The whole world is not New York. There are some people out there who like me," he says. "You [writers] don't always help, but there are some people out there who like me." His delivery is curt. There's a flash of spite in his eyes. You halfway expect him to put his hands on his hips and stomp his feet. You don't see a hero or a god so much as a kid whose feelings are hurt. The disjunction between the cage and the comment is startling, but not unprecedented.

Back in May, coming off a frustrating series with Boston, Rodriguez spoke about his longing for acceptance: "We can win three World Series and with me it's never going to be over. My benchmark is so high that no matter what I do, it's never going to be enough." You can see, even from a distance, the mark the boos and the criticisms have left. "It hurts him," Yankees manager Joe Torre says. "He's a sensitive guy."

"Sensitive" isn't a word you hear in reference to ballplayers all that often — R&B singers are sensitive, dancers are sensitive; ballplayers are "nails," "stones," "guts" — but it's a firmly entrenched part of the A-Rod discourse. As his troubles at the plate and in the field have mounted this summer, it has become codified, definitive, a constitutional quality at the root of his failings. He feels too much. He cares too much. He strikes out four times in a game — the pressure is getting to him. He throws another groundball away — he's deep in his head.

In an unguarded moment in late June, Rodriguez actually told the New York media he was "trying way too hard" and admitted boos from the home crowd were getting to him "a little bit" (a couple of soft-flesh-beneath-the-turtle-shell moments he wishes he could have back, no doubt). But it doesn't even matter whether the "sensitive" tag is at all legit. What matters is that, in our eyes, he wears it. In everything he does.

We also key on what appears to be a constant calculation on A-Rod's part, about what to say, with whom, when and where. In late June, with the Yankees down a run in the 12th inning against Atlanta, he stands in against Jorge Sosa, with Jason Giambi on first, and goes yard for the win. The crowd goes wild, A-Rod throws his helmet in the air and takes a slow trot around the bases. Finally, a walk-off. Finally, a David Ortiz moment — if you look closely at the footage, you can see the monkey tumbling ass-over-teakettle off Rodriguez's back. He's happy. His teammates are happy. The fans are happy. Everyone's feeling good. But in the postgame interview, he gums things up a bit.

"I know the boys are waiting on me, and the boys know what I can do," he says. "And it was like, 'Finally, I picked the boys up.'"

If you're scoring at home, that's three "the boys" in the space of 26 words and two sentences. And who says "the boys," anyway? Kid Gleason says "the boys" in "Eight Men Out," I think. Maybe in "Bull Durham" someone says "the boys," but if anyone does, he doesn't mean it. Nobody says "the boys." The line sounds forced, scripted, a nod toward a kind of camaraderie that seems not to exist between him and his teammates anyway. It's as if he's playing a scene from a film, as if he has thought ahead of time about what he'll say when he finally hits a walk-off, as if this is what you're supposed to say when you and "the boys" are jubilant.

"He has kind of an Eddie Haskell public persona," says Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Art Thiel, a press-box regular during A-Rod's seven seasons with the Mariners. "He always appears to say and do what he thinks the audience in front of him wants."

In spring training this year, perhaps consciously working against the perception that he's too polished, Rodriguez began dropping F-bombs and generally cussing more in conversations and interviews with beat writers. "It was out of nowhere," says Peter Abraham of The Journal News in suburban New York. "It sounded weird, like it wasn't even him." Rodriguez isn't being devious or malicious in such moments, but he's shape-shifting, like campaign-trail Bill Clinton, and we begin to wonder who the real guy is, and whether there's a core that defines him.

"I think he thinks his success is predicated on self-control, on physical self-control," says Keith Olbermann of MSNBC and ESPN Radio. "But it means he acts — in what he says, in the gestures he makes when he hits a home run or a double, like a ballet dancer trying to memorize his steps. He aims to please. He never just lets it wail."

More than the idea of his fat contract (only half of his yearly salary is paid by the Yankees; they pay significantly more for Jeter); more than the idea that he can't win (big-ticket teammates Giambi and Mike Mussina have never won it all, either); and more than the idea that he doesn't produce in crunch time (he literally carried the Yankees in the 2004 division series against the Twins, hitting .421/.476/.737), it's this perception of A-Rod as someone vulnerable to his own feelings and as someone deeply concerned about the opinions of others that rankles us. To borrow a line from Willie Nelson, our heroes have always been cowboys: Jeter, the plainspoken stalwart who never shrinks from the moment; Ortiz, the self-possessed lover of life who relishes high-stakes at-bats. We can digest these guys, can admire them in a romantic, uncomplicated way. They seem to make no demands on us at all. Their identities, their roles in our imagination appear fixed, clear and consistent.

A-Rod, on the other hand, comes off as this odd blend of superstar talent and confidence, packaged with common-guy uncertainty and instability. He's someone we have to think about. What makes him tick? How's he holding up? Is being in the fishbowl getting to him? Someone we have to engage on a kind of basic human level.

"It's complicated with A-Rod," says Steven Goldman, author of the Pinstriped Bible at YesNetwork.com. "It's about us, too — writers, fans, whomever — about how we respond to him. Can we accept him; can we empathize with the possibility that he has weaknesses just like any of us? Or do we reject him? Do we make fun of him and distance ourselves from him? It's like an after-school special almost."

Everyone says, "It's hard to have sympathy for a guy making $252 million." We struggle to see ourselves in someone so wealthy and so talent-rich. The guy is so good, and at such a young age, that we literally have no analogs for him in our experience. We don't relate. He strikes us as robotic, as impossibly skilled. We can't sympathize. But empathy is a different impulse.

Empathy means stepping outside ourselves and our conventions. We don't really know what kind of stress A-Rod feels, but empathy would have us wonder. Empathy would have us thinking about how "sensitive" might be the flip side of "passionate." Empathy also could mean imagining how opening up to the media, or being vulnerable to the people, wouldn't be the easiest thing in the world for a guy who has been under the microscope since he was a teenage kid growing up in Miami without a father. It would mean being emotionally entangled, responsible even.

Most of us reject that prospect. We run from it. We prefer the simple, familiar mechanics of winners and losers, heroes and villains, guys who have it and guys who don't. We say it's all about the rings. We say, as if we have no weaknesses ourselves, as if we've never shrunk from anything in our personal or professional lives, "suck it up" and "be a man." We demonize, then exile the "weak" guy. We treat him as if his sensitivities were contagious, as if he had cooties.

Once that die is cast and he's outside the realm of empathy, we can have our way with him, even if the way we do him seems wildly out of whack with his performance.

"He's held to an impossibly high standard," Kay says. "I really believe they expect him to get a hit every time up. The guy gets his temperature taken every single at-bat."

And he's found wanting. Every single time. Every single time he collects a check. Every single time Jeter makes a play or Papi goes deep. And every single time he takes his shirt off in the park. It's all fair game.

What's often lost in this game is the fact the guy is ridiculously good. Once-in-a-generation good. "He can only be compared with some of the best infielders in baseball history," Baseball Prospectus' Joe Sheehan says. "We're talking about someone who's already one of the top 25 players ever, and who will probably end up as one of the 10 best."

Will we ever come around to him? A world championship ring or some dramatic October heroics would go a long way, no doubt. We've seen big-time transformations in the past. Before winning his first Wimbledon, Andre Agassi was an image-conscious punk. Until the Bulls beat the Lakers in '91, Michael Jordan was a me-first highlight reel who didn't make the players around him better. Not until his Masters victory in 2004 did Phil Mickelson begin to shed his reputation as an empty talent who couldn't handle the big moment. Before his back-to-back Super Bowl titles, John Elway was a gunslinger who couldn't truly lead.

But although a ring would put A-Rod in a familiar category, the more interesting, and more likely scenario (the Yankees are an aging, pitching-weak team) is that things continue on the track they're on now. He's only 31, and we've had Bonds and Clemens to concentrate on these past 10 years, but if A-Rod stays healthy and productive in the years to come, it will become increasingly clear that he is hands-down the best player in the game, and is very likely the best all-around player any of us will ever have the privilege to see in person. Even without a title. Even with what we think is a sensitive heart. Even with what we perceive to be a scripted tongue.

As he makes his way toward some of the all-time records, will we soften our A-Rod stance and expand the register of what we can connect with, express empathy for? Or will we hold to the old tough-guy standards and keep doing him the way we do?

It's on us, not him, from here on out.

Posted by Steve Kenul at 1:49 PM

Posted by Steve Kenul at 1:49 PM

« Home

« Home